The Louisiana Environment

The EPA's Superfund Program in Louisiana

by Robert Stein

Louisiana is one of the most

polluted states in the union, a result of years of extracting resources

and inappropriately disposing of hazardous materials. In an effort

to combat this trend, the Environmental Protection Agency established the

Superfund program in 1980. The Comprehensive Environmental Response,

Compensation, and Liability Act (enacted Dec. 11, 1980) set up rules and

prerequisites for hazardous sites, attempted to find liable parties for

each site, and founded a fund for cleaning them up. Under CERCLA,

the Superfund program is managed by the Comprehensive Environmental Response,

Compensation, and Liability Information System (CERCLIS). The Superfund

program works with state and tribal governments to reduce or repair the

damaged caused by years of pollution. It is CERCLIS’ job to seek

out, evaluate, and declare potential Superfund sites.

In addition, CERCLA provides

two types of “response actions”: short-term removals for sites which demand

promptness, and long-term “remedial response actions,” to be performed

only at National Priorities List (NPL) sites. An NPL site is chosen

by the EPA through CERCLIS. Sites are first identified, then surveyed,

assessed, and inspected by a field team. A ranking of 28.5 or higher

on the “EPA Hazard Ranking System” (based on ground water, surface water,

and air), will place the site on the NPL list. If the site does not

make the list, it becomes the state’s responsibility to clean it up.

After a site has been chosen, money will be allocated by CERCLIS

and the clean up process can begin. Alternative methods of finance

include funding by the responsible party (voluntarily or through legal

action), and state or local government funding. If physical construction

is completed and a Final Close Out Report is approved, the site will be

removed from the NPL list. Since the Superfund program began, over

600 sites have been brought to this “construction complete” phase.

The EPA has divided the U.S.

into ten regions to organize the clean up of these NPL sites. The

state of Louisiana is part of region six, which also includes Texas, Oklahoma,

Arkansas, and New Mexico. Currently there are twenty-one Superfund

sites in Louisiana (see site list on next page.) From the Southern

Shipbuilding site in Slidell to the American Creosote Works in Winnfield,

the EPA has been in Louisiana since the beginning of the Superfund Program.

The Superfund plays a particularly crucial role in Louisiana, cleaning

up sites surrounded by low-income minority communities.

Currently there are nine

NPL sites in Louisiana which have reached the “construction completion”

phase. The first site to be completed was Bayou Sorrel (LAD980745541)

on May 6, 1992. Locally known as Grand River Pits, this site is situated

about twenty miles southwest of Baton Rouge. For about ten years,

Grand River Pits was home to an injection well storing herbicides and pesticides.

The facility was managed by EPAC, who (along with its sister company, CLAW

Inc.) are held as the PRP’s. At a cost of $28,700,000, a geomembrane

cap with slurry walls and a gas venting system were installed. Additionally,

a ground water monitoring system was put in place to ensure the purity

of the nearby aquifer. Construction began in 1988 and was finished

in 1990, providing protection against contact with the contaminated water

and soil. The site was then reviewed at the first of several post

construction tours and declared complete.

Only about 100 people live

within five miles of this site, but thousands more Louisiana residents

depend on water from the aquifer that lies beneath it. Wildlife and

game in the area also drink the same potentially contaminated water.

The EPA claims that pollutants are totally contained within the geomembrane,

and continues to monitor water in the Bayou Sorrel region.

(Graphic from http://www.epa.gov/earth1r6/6sf/sfsites/background.htm)

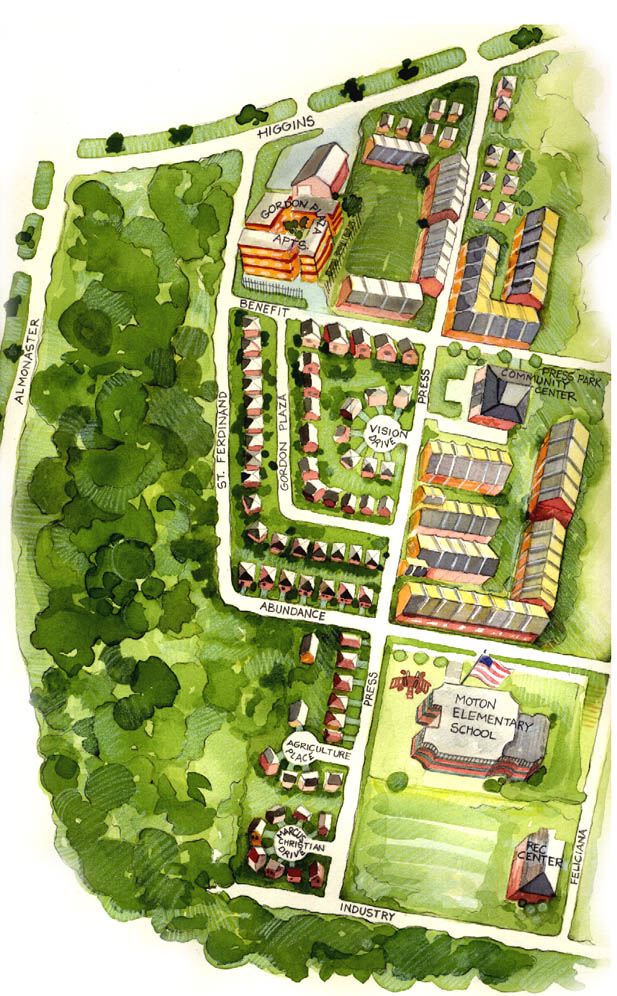

From 1909 to the 1950’s, the city of New Orleans owned and operated the Agricultural Street Landfill as a municipal site. It was reopened briefly in 1965 to store waste and debris from the damage caused by Hurricane Betsy. In the 1970-80’s the northeastern part of the site was developed into a residential neighborhood. Private residences, public housing, a community center, and a school/playground were built on forty-seven acres of landfill. When lead, arsenic, and carcinogenic polyaromatic hydrocarbons (cPAHs) were found in elevated levels during EPA tests, the site was placed on the NPL list, granting it access to Superfund money. The site was then divided up into five Operable Units (OUs). OU-1 is an 48 acre undeveloped portion of land and OU-2 is comprised of residential properties. OU-3 and OU-4 are the Community Center and the Moton Elementary School (Mugrauder Playground) respectively. The ground water in the area makes up OU-5.

In OU-1 the EPA is planning to install “a containment cover of geotextile fabric plus one foot of clean backfill. But the course is more difficult to plan for the other Operation Units because they are inhabited. The 42 acres of residential property that make up OU-2 contains single family homes, multi-family homes, and public housing. This land will be dug up to two feet and then a barrier to be placed in the soil. The EPA will then supply a clean topsoil fill and new landscaping. At the Community Center (OU-3), the course of action will be a two foot excavation of the two acre open area and the same treatment as OU-2. The Moton Elementary School and Mugrauer Playground have been closed because of the potential effect of the pollution on the children. The EPA chose no course of action for these areas because the soil has been found clean to a depth of four and one half feet. The ground water (OU-5) has been deemed contaminated, however it is not considered a source of drinking water because of saltwater intrusion. Therefore no further action will be done by the EPA at this site. Construction of OU-1 began in January of this year. Currently the EPA is sampling and testing the air around OU-1 to determine Total Suspended Particles (TSP) and Total Lead. Each of the 11 sub-divided areas will take from two to three weeks to complete. Weekly updates are posted at

http://www.epa.gov/earth1r6/6sf/sfsites/daily _paragraphs.htm.17

Over 1,000 residents of the neighborhood in OU-2 have joined together to seek reparations from the city of New Orleans, the Housing Authority of of New Orleans, and the School Board. For six-years the residents have attempted to join their law suits together as a single class action law suit. On September 15, 1999, after fourteen days of testimony, Judge Nadine Ramsey certified the case as class action. The mostly African-American plaintiffs seek reparations for reduced property values, moving costs, and regular medical checkups. Total reparations in the suit range from fifty to seventy million dollars.

Although the Thompson-Hayward

Chemical Plant is not yet an NPL site, the EPA is currently debating its

entrance into the Superfund program. Situated off Pine street near

Xavier University (Gert Town), the plant had been producing various poisons

from WWII to the 1970’s. Workers would feel their skin tingle and

burn beneath chemical suits while residents sat outside their houses.

The plant is now closed, but years of dumping pesticides, herbicides, and

fungicides down the drains have left all of these chemicals in the soil

underneath the surrounding residences. It also served as a storage

plant for dry-cleaning and other commercial chemicals during the 1980’s.

Signs of toxins were also found in the fat tissue of the neighborhood’s

longtime residents. Dust in local homes was found to contain DDT,

a poisonous pesticide banned in 1973. The waste is so toxic that

t is not cost-effective to store it in the U.S. Even before the Superfund

program could react, the state ordered the top four feet of the site and

over 75,000 gallons of waste water to be removed. The EPA is currently

testing the concentration of toxins at various distances from the plant,

so that they may determine the origin of the chemicals.

Like many other potential

NPL sites, the Thompson-Hayward chemical plant has changed ownership over

its many years of operation. Up until the 1970’s, this site was owned

by Phillips Electronics based in the Netherlands. Local residents

have filed a class-action law suit against its current owners, Harcos Chemical

Co. But since Harcos has only owned the plant for less than one half

of its history, it is unclear whether or not the residents have a strong

enough case. This change of ownership theme, prevalent in many gross

polluting industrial plants, also makes it very difficult for the EPA to

find a PRP. However reparations are needed to right the wrongs that

Gert Town citizens have endured for years. If the Thompson-Hayward

plant were to receive federal Superfund money, perhaps some of the issues

at hand could be solved comparatively easily. But without the EPA’s

assistance, neighbors living near the site seem to be temporarily out of

luck.

Through the Superfund Program, the EPA has made a serious effort at cleaning up some of the most polluted sites in the country. CERCLA and SARA provide a solid foundation for identifying and funding the clean up of hazardous waste sites. However, if there had been more legislative protection in the years during which these sites were operational, there would be no reason for the Superfund today. Thanks to the Superfund, Louisiana's environment has significantly improved. Almost one third of the NPL sites in this state have been cleaned up. Whether the current legislation and enforcement will safeguard our environment or just produce more Superfund sites, only time will tell.

Coyle, Pamela. “Landfill Site OK’d as Class Action.” Times-Picayune 21 Sept. 1999: A1, A5.

Schleifstein, Mark. “Danger at the Doorstep” Times-Picayune 29 Jan. 1995: A1, A4.

Smart, Tim. “The New Debate Over Superfund: How Clean is Clean Enough.” Business Week 13 July 1987: 34.

You can reach the EPA's Superfund program by e-mailing them at the Office of Emergency and Remedial Response: offutt.carolyn@epa.gov

To reach Region 6 (Louisiana's designated region) e-mail: r6.www@epa.gov.

For a complete copy of this essay e-mail me at stein_robert@hotmail.com

For a CERCLA overview from the EPA site:

http://www.epa.gov/superfund/whatissf/cercla.htm

For a backround of CERCLA by the ChemAlliance:

http://www.chemalliance.org/RegTools/back/back-cercla.asp

EPA's Superfund website:

http://www.epa.gov/superfund/index.htm

Region 6's (Louisiana's designated region) website:

http://www.epa.gov/earth1r6/6sf/6sf.htm

Agricultural Street Landfill, Project Backround:

http://www.epa.gov/earth1r6/6sf/sfsites/background.htm

Return to B. Fleury's Home Page

This page was last updated on 1/07/00