The deictic foundation of ideology, with reference to the African Renaissance

Willem J. Botha

1.1. Background

In 1994 the ideology of apartheid - an official policy of racial segregation, instigated and practiced for forty-six years by the former National Party - was abandoned in South Africa when the African National Congress became the majority party in a Government of National Unity. A new negotiated interim Constitution came into practice, which lead to the final Constitution of 1996, which has been adopted by a two-thirds majority by the Constitutional Assembly on 8 May 1996. After a few modifications the Final Constitution came into practice on 4 February 1997.

According to Rautenbach and Malherbe (1998: 4-5) this Constitution makes provision, amongst other things, for the supremacy of the Constitution, the entrenchment of a democratic system, the protection of every citizen's defined rights by a Bill of Rights, an independent Court, which includes the Constitutional Court, and (important for this paper) mechanisms (like a single citizenship and values for human dignity, equality, nonracism and nonsexism) in order to build a sole nation [emphasis mine]. In spite of the strive for a single nation, the Constitution also makes provision for diversity, by endorsing eleven official languages, nine provinces with semi-autonomous government, protection of different rights, regarding, amongst others, language rights, cultural rights, religious rights, women's and children's rights, recognition of traditional leaders, etcetera.

In broad terms the new South African society can be considered a democracy, a very young democracy, which has to grow within and according to the framework of the new Constitution. But the Constitution's effect on society has to be weighed, and dealt with, against the background of a previous dividing ideology of apartheid - an ideology which drew strict borders between categories of people, "(a)n official policy of racial segregation … , involving political, legal, and economic discrimination against nonwhites", according to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Even the concept "nonwhites" (from the definition) is a discriminating term that has been used frequently in the former South African society: as a defining criterion for the category "nonwhites". No "fuzzy boundaries" existed. A person would have been considered either in or out of the category of "whites".

The Constitution as such is an exponent of a sociopolitical ideology, "(a) set of doctrines or beliefs that form the basis of a political, economic, or other system," according to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. But an underlying "ideology", which relates to what the The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language calls a "body of ideas reflecting the social needs and aspirations of an individual, a group, a class, or a culture", acts as an impetus for this constitution: the need to build a sole nation, to invalidate former strict boundaries between categories; actually to create a new category with fuzzy boundaries - the "rainbow nation", a metaphor that is being used frequently by President Nelson Mandela, to describe the nation to be. This "hidden ideology" embodies a very rich blend of concepts under the surface, amongst others, concepts which are revealed in expressions like affirmative action, transformation, transition and truth and reconciliation. In view of the fact that the Constitution makes provision for diversity, this "hidden" ideology most probably results from a "presupposed inadequacy" of the Constitution as such.

The Deputy President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, further enriched the blend when he refined the metaphor rainbow nation in an effort to extend this category to include the subcategories of Africa. In his address to the Corporate Council Summit (Chantilly, Virginia, USA), in April 1997, he mentioned as an exponent of a new conceptual blend an African Renaissance towards which Africa is advancing. Since this event the concept of an African Renaissance became a driving force in the promotion of the idea of a rainbow nation and the rebirth of Africa. The concept of an African Renaissance actually originated (without explicit mentioning) in a preceding address delivered by Thabo Mbeki on 8 May 1996, when he made a statement on behalf of the ANC at the adoption of South Africa's 1996 constitution bill, in which he made the now acclaimed statement (metaphor):

(1) I am an African.

The investigation conducted for this paper, will focus on the emergence of an ideology from this address by Thabo Mbeki on 8 May 1996. The quote from his speech [example (1)] implies a trilateral coordinate system: identity; existence in time; and locality. As a deictic expression it portrays the three deictic categories: person, time and space.

Dealing with a long existing ideology it may well be the case that the deictic terminology could be expanded to include categories like social deixis and ideological deixis - although I consider them to be extensions of the basic deictic categories. Perhaps it could be best illustrated by the diminishing ideology of apartheid which existed for forty-six years. Some people were born and brought up within the "culture of apartheid". Like other social and cultural variables it shaped their lives. And, like many cultural indicators, it resided in language - especially the Afrikaans language. From this point of view the corresponding language expressions would reveal ideological deixis. This matter will not be dealt with in this paper. Examining an emerging ideology, we will focus on the fundamental deictic categories.

1.2. Points of departure

In this paper it will be assumed that any ideology has a deictic foundation in the sense that it originates within a certain (physical) space; it exists as an active ideology inside a certain time frame; it emanates from a person's (group of persons') cognitive and, frequently, emotional system; and it extends to many domains of existence and experience.

Time and space will not be dealt with explicitly. Within the category person deixis Mbeki's use of the pronoun first person singular in relation to the "I am an African"-metaphor will be focussed on. It will be pointed out

· that the communicative structure of an ideology resembles the speech act structure;

· that the speaker's cognitive and emotional input determines a "degree of alliance" in accordance with the proximity schema;

· that the categories first person singular/plural are cognitively manipulated;

· that the speaker (conceptualizer) makes different vantage point shifts in order to expand the different categories to accommodate as much as possible individuals within a certain spatial (cognitive) domain;

· that the resulting perspective and viewpoint transfers imply conceptual identity transformations.

In conclusion, the conceptual blend of an African Renaissance will be viewed in relation to the phenomenon of conceptual categorization and recategorization.

2. The communicative structure of an ideology

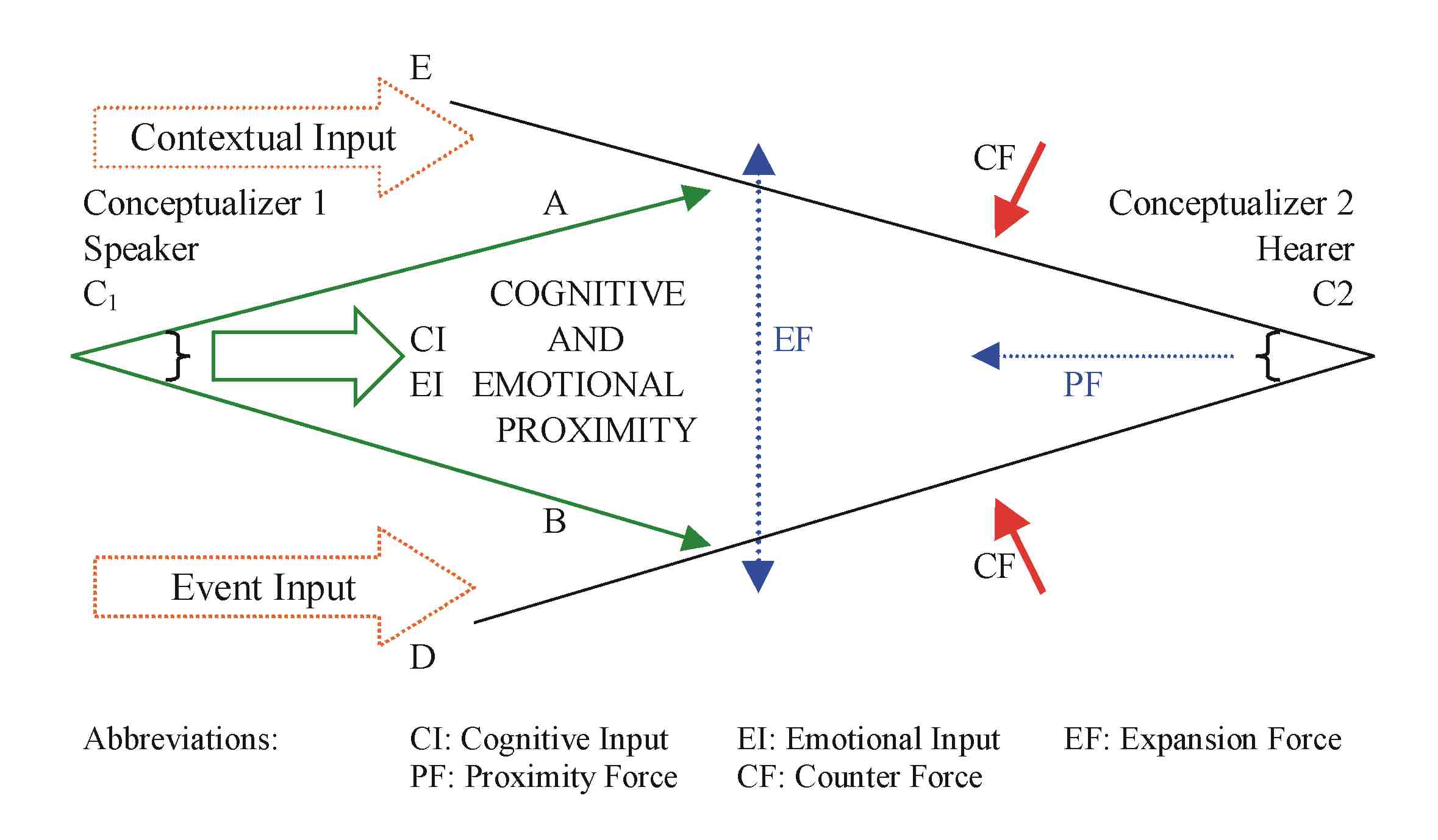

From time to time (or over a continuation of time) an individual or group of individuals promote or sustain a specific ideology by way of language use (and/or other means they wish to apply, which will not be examined in this paper) in an effort to effect potential "believers" and followers of such an ideology. The emergence and perpetuation of such an ideology depends on the "illocutionary force" underlying the ideas or collective views held by a group of people over a certain period of time. Consequently a living ideology can be considered a macro speech act. With reference to Figure 1, which represents an extension of a model proposed by Delport (1998: 44), we will examine this phenomenon.

Figure 1 exemplifies, as an analogy of a speech act, the structuring of a dogmatic intent of a representative (or representatives) of a certain ideology. Conceptualizer 1 (as an agent of a certain ideology) has to change the views of Conceptualizer 2 in an effort to promote the specific ideology. In speech act terms we can say that the illocution of the speech act is directed to an addressee in order to establish a certain perlocution: cognitive and emotional proximity to the group which C1 represents in favor of an attitude of solidarity, or adherence, or alliance, or conformity, or … etcetera - in agreement with the specific intent. C1 strives to expand the angle EC2D by way of conceptual and emotional input. In this regard emotional input refers to emotional stimuli conveyed by language, which instigates what Goleman (1996: 293) calls

a second kind of emotional reaction, … , which simmers and brews first in our thoughts before it leads to feeling. … In this kind of emotional reaction there is a more extended appraisal; our thoughts - cognition - play the key role in determining what emotions will be roused.

The abbreviation CF represents counter-forces that may restrict the ideological perlocution. It may come from contextual and event inputs; but also from emotional and cognitive activity.

Angle AC1B represents the expansion of conceptual and emotional input on account of a force created by the linguistic application of specific cognitive devices. Amongst these cognitive mechanisms are the conceptual manipulation of the pronoun first person singular (in accordance with maneuvering strategies involving reference-point phenomena) and metonymic and metaphorical extensions. Other input variables, such as the contextual and cultural state of affairs and/or specific physical or emotional events, may affect the underlying strength of the expansion force. The two interacting communicative forces (expansion and proximity) instigated by the cognitive and emotional input are inversely proportional. From an ideological (and theoretical) point of view the objective would be that the proximity between the two confronting angles (AC1B and EC2D) would progress to such a limit that they eventually become a straight line EAC1C2BD, where the relation I:you becomes we. This objective relates to the proximity force which is based on gravity, i.e. attraction towards the speaker.

The two underlying communicative forces relate to two basic image schemas: proximity and container. C1 makes his/her "ideological assault" on the basis of these two experiential schemas. For the addressee (C2) to inevitably refer to we to express his/her affiliation to the group that C1 represents, he/she has to "feel" close (proximity schema) to the specific group. If C2 is narrow-minded (based on the container-schema), "(l)acking tolerance, breadth of view, or sympathy" - according to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, then it would be more difficult to "open" the angle EC2D; while an open-minded C2 (based on the container-schema), "(h)aving or showing receptiveness to new and different ideas or the opinions of others" - according to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, will be more prone to an expansive force created by manipulated cognitive mechanisms.

Against this background we will investigate such conceptual strategies relating to the pronouns first person singular/plural. To establish, maintain and expand mental contact, the pronoun first person singular functions as a very salient cognitive reference point on account of its extraordinary use. Before we explore the manipulating features of such an utilization, we have to emphasize the deictic fundamentals relating to the phenomenon cognitive reference point. It will be based on Langacker's (1993: 1-38) account of reference-point constructions.

3. Deixis and the coordinates of existence

3.1. The coordinates of existence

Human entities exist in a certain space at a certain point in time. And spatio-temporal cognizance implies identity. The coordinates of existence, i.e. identity, space and time, involves, inter alia, vantage point, view point, perspective and orientation - and an explicit or implicit knowledge of these spatial variables at a certain point in time. But conceptual awareness of these variables presupposes a certain alignment in relation to external reference points: spatial, temporal, or to other identities in space and time. The proximity image schema acts as a preconceptual base in order to link these reference points. In view of the experience of proximity, one has a closer relationship to comforting entities and situations, and a more distant relation to discomforting entities and situations. Taylor (1996: 134) rightly claims that the "degree of emotional involvement and the possibility of mutual influence are understood in terms of proximity." Compare for instance how the use of the verb come in example (2) suggests a comforting effect of closeness, while the use of the verb depart in example (3) indicates alienation from unpleasant entities:

(2) Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest (Bible: Matthew, 11: 8).

(3) Then shall he say also unto them on the left hand, Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels (Bible: Matthew, 25: 41).

3.2. Deixis and reference-point constructions

Langacker (1993: 1) claims that language structure provides significant clues about basic mental phenomena. In this regard he mentions the following notions that have general psychological importance, and which are founded on linguistic evidence: force dynamics; image schemas; subjective versus objective construal; and correspondence across cognitive domains or mental spaces. He considers cognitive reference point as a similar construct.

Against the background of what he calls image-schematic abilities (on a level more abstract than image schemas as such), Langacker (1993: 5) describes the reference-point phenomenon as "the ability to invoke the conception of one entity for purposes of establishing mental contact with another, i.e., to single it out for individual conscious awareness." He further asserts that reference-point ability remains below the surface of explicit observation. With regard to the reference point, Langacker (1993: 6) observes a few features which I consider to be very relevant to deixis as such:

· The reference point has an intrinsic or contextually determined cognitive salience.

· The salience feature of a reference point (R) functions in a dynamic way. It implies that a potential reference point must, first of all, have the capacity of significance to be a reference point; it then must become the focus of the conceptualizer's (C) conception, thereby allowing C to activate any element in its dominion as a target of conception in relation to R. This process could be recursive (compare Langacker, 1993: 6).

According to this view we can postulate that (external) deictic linguistic expressions are manifestations of such a reference-point ability, although it also embrace the ability to apply orientational image schemas, such as proximity, up vs. down, left vs. right, in front of vs. behind. From this point of view the referential competency of secondary deictic expressions is based on the reference-point ability instituted by the deictic center. Consequently the adverb then reveals that it is conceptualized in accordance with the reference point NOW (explicated by the deictic adverb now), the adverb there is conceptualized with regard to the reference point HERE ( explicated by the deictic adverb here), and the different pronouns are conceptualized in accordance with the reference point SPEAKER (explicated by the pronoun I).

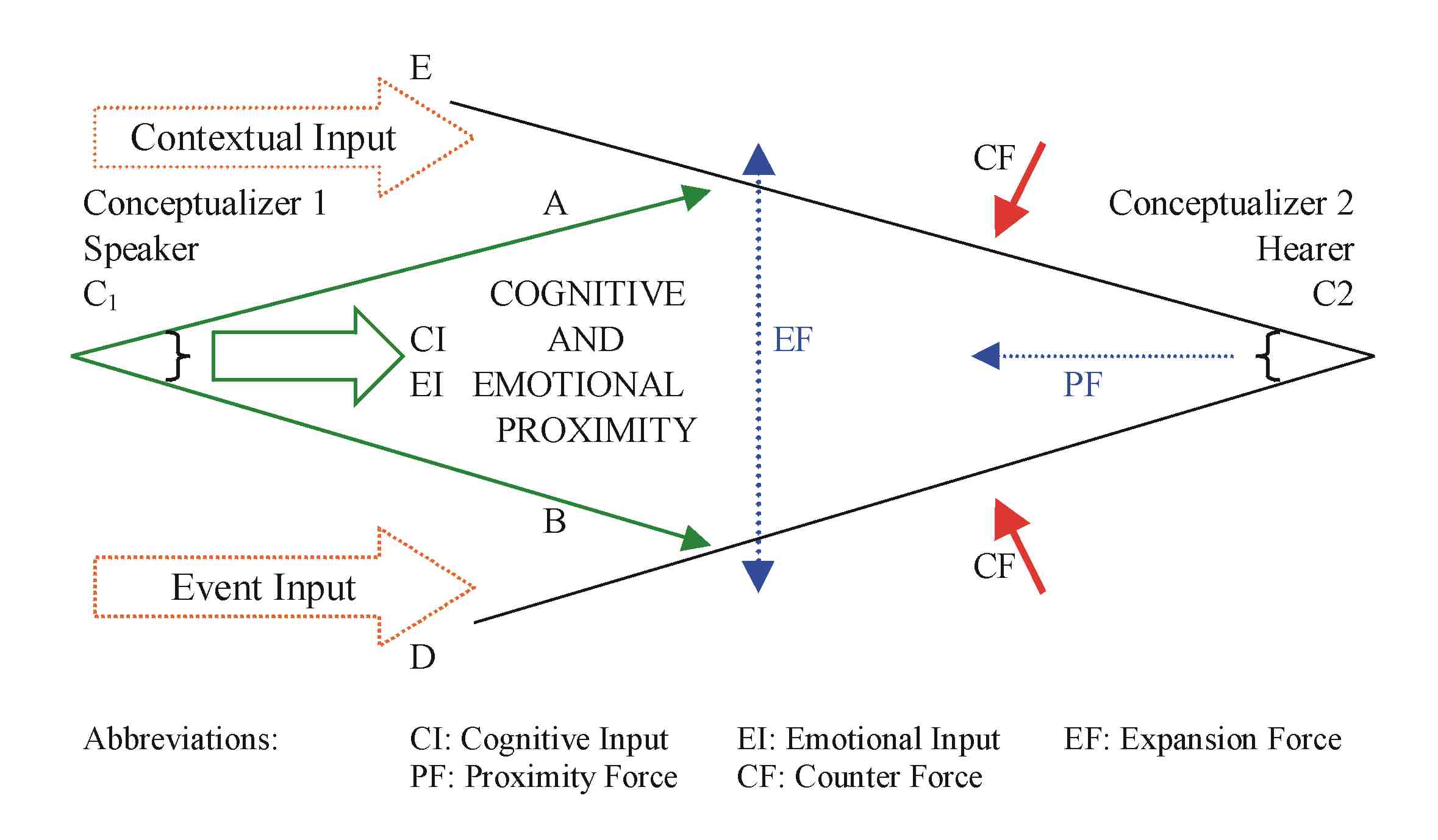

Profiled in language, all the above-mentioned coordinates relate to the deictic center. Figure 2 represents the fundamental features of the deictic center: the pronoun I, which reveals the (role) identity of a speaker; the adverb now, which indicates the moment of speaking; and the adverb here, revealing the time of speaking. This trilateral coordinate system, represented by the above-mentioned words, defines the primary level of deixis, namely the deictic center. On a secondary level pronouns like he, she, it, they (if not used anaphorically) and you (singular and plural) refer to entities in relation to I; their meanings are contextually related to the meaning of the pronoun first person singular. Accordingly, now (within the deictic center) functions as a cognitive reference point for the time deictic adverbs then, yesterday, etcetera; while here acts as a cognitive reference point for the space deictic adverb there. Although we is plural and its meaning is linked to I, it is not the plural form of I. Therefore it is also placed outside the deictic center. We will closely investigate the deictic relation between I and we, due to the fact that they are category-referring expressions and (within an ideological context) ideology-referring expressions.

Taking these theoretical presuppositions into consideration,

we will investigate the manipulated use of the pronoun first person singular

(I) with regard to Mbeki's I am an African-address. 4. The pronoun categories first person

singular/plural 4.1. Role and identity As was pointed out, the pronoun I (first

person singular) is generally used to identify the speaker, to establish a role

category for the speech act initiator. We will name it the canonical use of the pronoun

first person singular. First of all the pronoun I designates the speech

act role (identity) of the speaker, it serves as an implicit cognitive reference

point in order to establish mental contact with an addressee/hearer. But speakers

have different roles in society, roles that contribute to specific identities, which

are very often linguistically revealed, as is pointed out by Crystal (1987: 17): The linguistic signals we unwittingly transmit

about ourselves every moment of our waking day are highly distinctive and discriminating.

More than anything else, language shows we 'belong', providing the most natural badge,

or symbol, of public and private identity. The reference-point phenomenon (mentioned above)

is very fundamental and pervasive in our everyday experiences, although we are largely

unaware of it (cf. Langacker, 1993: 5). In accordance with his intentions, the

speaker may choose to exploit the salience of the pronoun first person singular

as a reference point in order to manipulate the degree of mental (and emotional)

contact with an addressee/hearer. Depending on contextual circumstances, he can manipulate

the meaning of the pronoun first person singular (I) in such a way

that it can be extended to refer to the addressee, to somebody outside the domain

of the speech act, and to a group of persons - as it is the case with the pronoun

first person plural (we), which can be used (apart from its inclusive

and exclusive utilization) to refer to the speaker, a group of entities from which

the speaker is excluded but with whom he/she identifies on account of social or ideological

cohesion, or to disclose his/her solidarity with a category of entities as such.

Compare Botha (1980: 5-22) for an elaboration on this matter, and examples taken

from the Afrikaans language. 4.2. Conceptual manipulation of the pronoun first

person singular In his address of 2 042 words (63 paragraphs)

on 8 May 1996, when he made a statement on behalf of the ANC at the adoption of South

Africa's 1996 constitution bill, Mbeki's use of the pronoun first person singular

is very discrete. In order to examine it, his address was artificially divided into

five equal sections of 408 words each, except for the last section which contains

410 words. We will refer to sections A, B, C, D, and E respectively. At contextually

strategic places, that is within each of these sections, the cohesive metaphor I

am an African is explicitly mentioned once to serve as an element of conceptual

coherence. Before we analyze his usage of the specific metaphor,

we will investigate the usage of I within the relevant context. 4.2.1. Reference-point strategy The selection of I instead of we in

a certain context discloses what can be called a reference-point strategy. A person

with a very prominent identity, as the Deputy President of South Africa (Mbeki),

can select I instead of we as a reference point to constitute a contextually

determined cognitive salience, in order to establish mental contact with an addressee

(C2) - what he indeed does. In addition, the speaker (C1) can magnify his own reference-point

status by an appropriate speech act: a commissive which commits the speaker

in doing something in the future, or an expressive in which the speaker expresses

feelings and attitudes about something (cf. Longman, 1985: 265). However, as

the contextual reference point the prototypical speaker (C1) has the ability to activate

within the resulting conceptual dominion of the speech act the addressee as a target

of conception in relation to himself - by explicitly addressing C2 as you,

but also by the selection of the specific speech act: a declarative, which

changes the state of affairs in the world (for the addressee); a directive,

activating the addressee to do something (cf. Longman, 1985: 265). For ideological purposes the expressive would have

been an ideal speech act for Mbeki. It would have given him the opportunity to explicitly

express his ideological views and wishes. However, he decides on the predominant

use of the representative as a speech act, "which describes states or

events in the world, such as an assertion, a claim, a report" (cf. Longman,

1985: 266). In addition he never mentions you (the word you does

not even occur in the address), although he aims at a blend between I and

you, resulting in a solidifying we. 4.2.2. Expanding the category first person

singular By exploiting his reference-point status as speaker,

implicitly referring to an addressee by using I (and within a diverse group

of addressees also to a third person), Mbeki actually expands the category first

person singular to include different extensions. We will look at a few of his

extensions in relation to the prototype of the category first person singular: · The first usage

of the first person singular occurs after a general description of the typical

South African landscape, with its specific fauna and flora. He concludes with: (4) A human presence among all these, a feature

on the face of our native land thus defined, I know that none dare challenge me when

I say - I am an African! No reference is made to the specific identity of

I. The pronoun first person singular is actually used in a collective

sense; for pure referential purposes it could have been replaced by we. · In a next phase

Mbeki makes identity and vantage point shifts, by using the first person singular,

to accommodate subcategories of the South African nation and to present an explicit

or implicit historical perspective as an integral substance of the nation to be.

The intent most probably would be that the resulting conceptual identity transformations

should have a consolidating effect on different subcategories of the intended rainbow

nation: (5) I owe my being to the Khoi and the San whose

desolate souls haunt the great expanses of the beautiful Cape (reference to the

Khoi and the San). (6) I am formed of the migrant who left Europe

to find a new home on our native land (reference to the white South African immigrant

from Europe). (7) In my veins courses the blood of the Malay

slaves who came from the East (reference to the Malay people from the East). (8) I am the grandchild of the warrior men and

women that Hintsa and Sekhukhune led (reference to the indigenous tribes of South

Africa). An interlude occurs when at this stage in the chronology

of the address Mbeki reaches out to the all-inclusive context of Africa. An identity

and vantage point shift to the collective first person singular takes place

to harmonize with elements of an extended Africa. In addition to the I am an African-metaphor,

an African Renaissance is also suggested here: (9) My mind and my knowledge of myself is formed

by the victories that are the jewels in our African crown, the victories we earned

from Isandhlwana to Khartoum, as Ethiopians and as the Ashand of Ghana, as the Berbers

of the desert. Mbeki immediately after this view makes a conceptual

shift again when he returns to certain subcategories of the nation to be, and speaks

on their behalf: (10) I am the grandchild who lays fresh flowers

on the Boer graves of St Helena and the Bahamas, who sees in the mind's eye and suffers

the suffering of a simple peasant folk, death, concentration camps, destroyed homesteads,

a dream in ruins. The identity and vantage point shift is made to accommodate

a subcategory of the South African nation consisting mainly of a Afrikaansspeaking

subsection of the intended rainbow nation whose ancestors fought two wars against

the British. A historical perspective is also implied. Immediately afterwards the

first person singular is transformed to accommodate the subcategories Indians

and Chinese: (11) I come of those who were transported from

India and China. This phase of the address is ended with the I

am an African-conclusion, a metaphor which serves as a cohesive tie to resonate

African solidarity. The phrase (b)eing part of all these people in example

(12) suggests the different vantage point shifts that took place in the preceding

section of the address, conceptual transformations aimed at expanding the category

first person singular for ideological reasons: (12) Being part of all these people, and in the

knowledge that none dare contest that assertion, I shall claim that - I am an African! · But Mbeki also

had to solidify those people who were nearer to him during a time, which was known

as a time of struggle, and the previously mentioned groups - in such a way that he

would not disunite one from the other. And the best way he went about, was to include

them very cautiously within his category first person singular: (13) I have seen our country torn asunder as these,

all of whom are my people, engaged one another in a titanic battle. (14) I have seen what happens when one person

has superiority of force over another, when the stronger appropriate to themselves

the prerogative even to annul the injunction that God created all men and women in

His image. (15) I know what it signifies when race and colour

are used to determine who is human and who, sub-human. (16) I have seen the destruction of all sense

of self-esteem, the consequent striving to be what one is not, simply to acquire

some of the benefits which those who had imposed themselves as masters had ensured

that they enjoyed. (17) I have experience of the situation in which

race and colour is used to enrich some and impoverish the rest. (18) I have seen the corruption of minds and souls

as a result of the pursuit of an ignoble effort to perpetuate a veritable crime against

humanity. (19) I have seen concrete expression of the denial

of the dignity of a human being emanating from the conscious and systematic oppressive

and repressive activities of other human beings. The views expressed in examples (13) to (19) could

easily impede the force of attraction aimed at every subcategory of the appropriate

group (intended rainbow nation) if the formulation lacks strategy. In the examples

the use of the specific verbs aid the ideological strategy in such a way that the

speaker is placed as a neutral observer somewhere in the category first person

singular - in such a way that he does not explicitly associate with a particular

group. Compare the use of the phrase I have seen five times; the phrase I

know also signifies a degree of impartiality. Although the phrase I have experience

indicates bias, it is only used once within this phase of the address. With his use of the first person singular

the speaker actually "grasps" (applies the proximity force, which is a

force of attraction - cf. Figure 1) the addressee into the deictic center. In this

regard I has a stronger solidifying influence than we. Although his use of the first person singular

is very notable and distinct within this specific context, it has to be viewed in

relation to his use of the first person plural, which can refer to different

groups within a heterogeneous South African society. 4.3. Contextual arrangement of the pronouns first

person singular/plural In South Africa a very complex blend, African

Renaissance (compare section 6), is emerging - also on a formal basis by way

of official working groups founded to promote the idea. In proclaiming the idea of

an African Renaissance, different people (individually, or as representatives of

a specific group or groups) at different times address people in an effort to establish

ideological cohesion. In their efforts they can use the pronoun first person plural

(we), to refer to the present (and future) followers of the idea, and, like

in the case of Mbeki, the pronoun first person singular (I). Although

Mbeki uses the pronoun first person plural rather frequently, it almost becomes

hidden within the specific context, owing to his prominent use of the pronoun first

person singular, but also in view of the fact that the status of his address

(on behalf of the ANC) could have limited the category first person plural

remarkably, and therefore would have been contrary to expectations regarding his

ideological aims. As was pointed out, Mbeki's use of the pronoun first

person singular is very distinct. However, it has to be viewed contextually in

relation to the use of other pronouns in his address. In order to examine certain

trends, the above-mentioned artificial division of his address into five equal sections

(compare section 4.2) will serve as framework for the investigation. For the purpose

of a trend analysis we grouped the subject, object and possessive use of each category

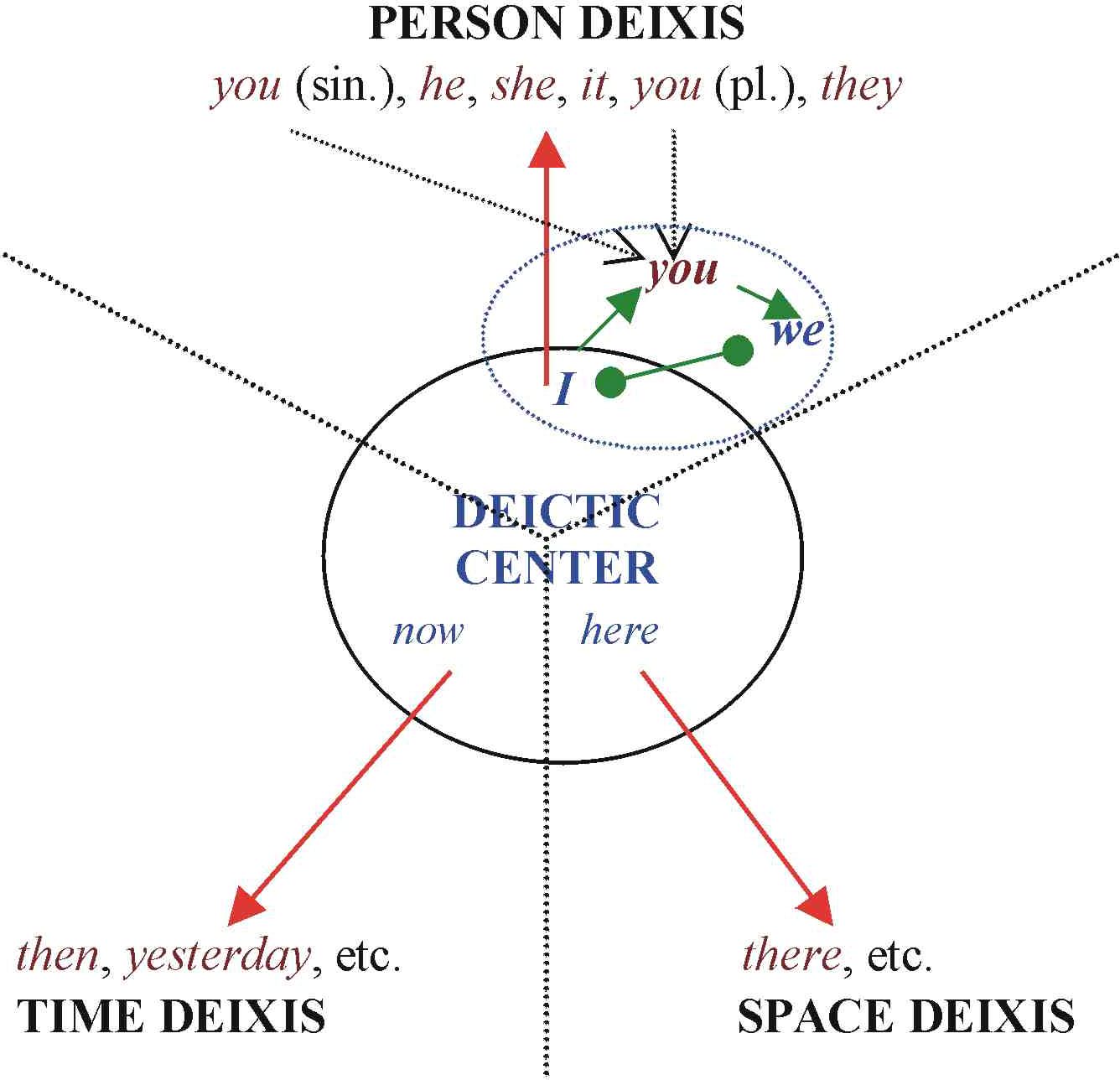

together. The graph in Figure 3 represents such a statistical breakdown. The diagram clearly indicates an upward trend in

the use of the pronoun first person plural, while the use of the pronoun first

person singular is trending down. Compare, for instance, the frequency of use

of the variables of the pronoun first person plural in the last paragraph

of the address: (20) Whoever we may be, whatever our

immediate interest, however much we carry baggage from our

past, however much we have been caught by the fashion of cynicism and loss

of faith in the capacity of the people, let us err today and say - nothing

can stop us now! The frequency of use of the pronoun first person

plural in section A is slightly misleading if we do not take into account that

the possessive our represents 11 of the 15 occurrences; compare Table 1.

Figure 2. The deictic center

Figure 3. Pronoun trends within

a specific context

|

Section A |

Section B |

Section C |

Section D |

Section E |

Total |

|

| I |

8 |

12 |

8 |

1 |

4 |

33 |

| my |

6 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

13 |

| me |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| we |

2 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

10 |

19 |

| us |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

8 |

| our |

11 |

2 |

4 |

6 |

7 |

30 |

| ourselves |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

3 |

7 |

| Total: |

30 |

22 |

14 |

17 |

29 |

112 |

In this regard we have to mention that the possessive our acts as a reference point which aids the mental path to a conceptual target. And as such it has less conceptual prominence than the target. Accordingly, it is conceptually less salient than we or us.

These trends distinctly correlate with Mbeki's underlying ideological intent: the relation I:you should become we. But the category first person plural is very fluid. It can single out the speaker (when we utilize the royal we), or it can include different numbers of individuals - even with the exclusion of the speaker (when he/she only associates with a group by using we). But the idea of a sole nation (and an African Renaissance), which he is aiming at in his address, would be futile without reference to we. In view of the fact that he never uses the pronoun you to refer to a specific addressee (we mentioned that the word you does not even occur in his address), he has to apply other strategies to reach certain individuals or groups of individuals in an effort to accommodate them under the pronoun we, within the boundaries that he determines for we. A vantage point shift enables him to do just that - a vantage point shift underlying the utilization of the pronoun first person singular (I), which enables him to single out certain targeted groups. But in his efforts he has to be very careful not to alienate certain groups from him, especially not the group that he formally represents with this address, namely the ANC. Again a vantage point shift provides him with the means to elude the danger. Compare examples (21) and (22), which come from consecutive paragraphs:

(21) I am formed of the migrant who left Europe to find a new home on our native land.

(22) Whatever their own actions, they remain still, part of me.

The anaphoric employment of they and their to refer to the migrants who left Europe, positions the specific referents immediately outside the deictic center, and therefore outside a category that we may refer to. Similarly, the anaphoric they and their is made use of in not less than 33 instances in his address, in addition to the demonstrative use of these, those and themselves, which in themselves (as deictic/deictic-related expressions) suggest withdrawal. On a syntactical level this vantage point shift occurs within close conceptual reach, which can also be interpreted as a strategic employment (in accordance with his official representation), if we consider it against the background of what Radden (1992: 515) labels the "iconic proximity principle", which implies that "(c)onceptual distance … tends to match with linguistic distance, i.e., temporal distance in speaking and spatial distance in writing." His conceptual solidarity with other groups than those who he officially represents, is therefore very brief.

The employment of anaphoric expressions reveals a "catalyst"-strategy. The application of the pronoun first person singular instigates conceptual proximity on account of the fact that the deictic center is expanded in a certain direction to include individuals of special groups. However, in addition, the speaker does not use the pronoun first person plural (we) to express further alliance with the specific group. He actually withdraws again from the specific group by using anaphoric expressions to refer to the group. This strategy sanctions the vantage point shift to yet another group, and prevents "suction" into a subgroup. Consequently, the expansion of the deictic center to different subgroups constitutes a similar constant identifying value within each subgroup, with alliance as the intended objective.

The investigation up to this point has shown that Mbeki's manipulation of the first person singular, together with his expansion and limitation of the fuzzy boundaries of the category first person plural, enhance his ideological intent. Furthermore, as was pointed out, he uses the metaphor I am an African in a very phenomenal way to cohere the context accordingly. However, as a metaphor, this specific phrase promotes his ideological intent remarkably.

5. The metaphor I am an African

Lyons (1968: 388/89) mentions a distinction that is being drawn by logicians between the existential and different predicative functions of the English verb to be. He also states that among the predicative uses, the following distinctions are made:

(a) the identification of one identity with another (a = b: e.g. That man is John); (b) class-membership (b C: e.g. John is a Catholic, 'John is a member of a class of persons characterized as Catholic'); and (c) class-inclusion (C D: Catholics are Christians, 'The members of the class of persons characterized as Catholic are included among the members of the class of persons characterized as Christians').

Against the background of the previous discussion, the distinctions class-membership and class-inclusion seem to be very relevant. Mbeki's use of the metaphor I am an African is aimed at class-inclusion, with the promotion of the conceptual blend African Renaissance as ultimate objective. But this metaphor constitutes a very complex constellation of metaphors. On account of his catalytic manipulation of the pronoun first person singular he methodically creates implicit metaphors which designate subcategories of the main category African. Reiterated, some of the subcategories can be summarized as follows, followed in each instance by relevant quotes from the address:

A: The Khoi and San are Africans (I owe me being to the Khoi and San …)

B: White migrants are Africans (I am formed of the migrant who left Europe …)

C: Indigenous African tribes are Africans (I am the grandchild of the warrior men and women …)

D: Afrikaansspeaking people are Africans (I am the grandchild who lays fresh flowers on the Boer graves of St Helena …)

E: South African Indians and Chinese are Africans (I come of those who were transported from India and China …)

F: Previously oppressed are Africans (I am born of a people who would not tolerate oppression.)

Etcetera.

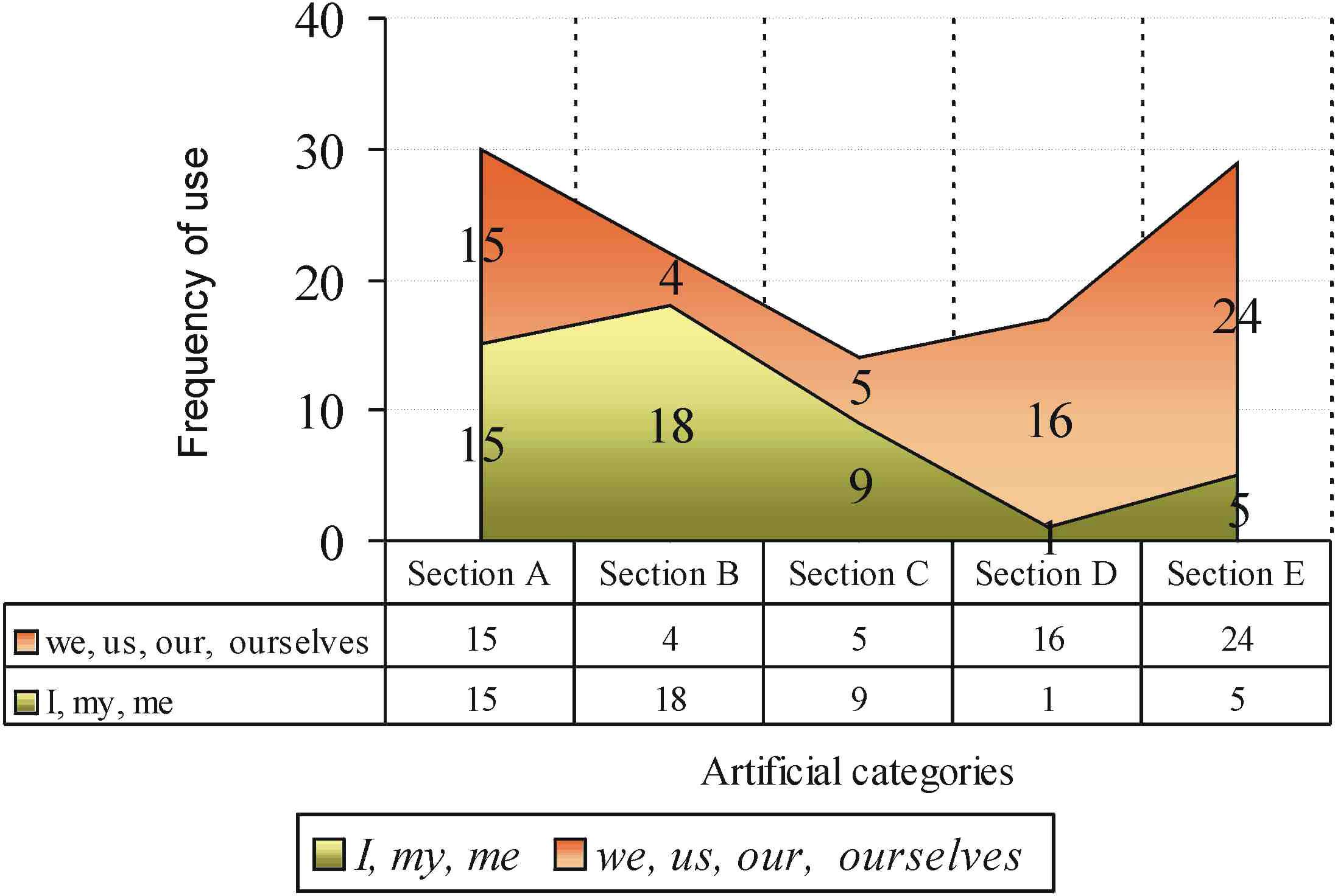

He defines the subcategories of Africans very cautiously by way of these implicit metaphors, not frequently using the typical I am X-phrase. He rather chooses to select different verbal phrases, like I am formed, I come of those, I have seen (many times), I am born of, etcetera - in an effort to establish a conceptual constellation of categories underlying the I am an African-metaphor. In accordance with Pauw (1996: 124) we represent this complex metaphor in the diagram in Figure 4.

He elucidates this conceptual constellation himself

when he postulates: (23) Being part of all these people, and in the

knowledge that none dare contest that assertion, I shall claim that - I am an African! But the assertion in (23) would have been less effective

if it had not been for the previous vantage point shifts made possible by the use

of the pronoun first person singular. The resulting (conceptual) identity

transformations actually enables him to penetrate different categories of people

on a conceptual level. Consequently, different addressees have to make perspective

and viewpoint transfers, with the intent to expand their categories - to replace

inflexible boundaries with "fuzzy" boundaries. In this respect the very

complex I am an African-metaphor has to support each perspective and viewpoint

transfer, implied by the diagram in Figure 4: the concept of an African is mapped

on each individual group, represented by I. Actually he aims at the pronoun

first person plural. Therefore the metaphor should actually have been: we

are Africans. But its effectiveness results from the fact that he uses I

instead of we, and in these instances the pronoun first person singular

functions on a metonymy-level. Langacker (1993: 30) points out that metonymy

is primarily a reference-point phenomenon, and that on a metonymic level people make

especially good reference points. As a very prominent South African Mbeki exploits

the deictic expression first person singular as a strategic conceptual reference

point in order to represent different categories in each instance. In essence it

relates to Langacker's (1993: 30) views in this regard: Metonymy is prevalent because our reference-point

ability is fundamental and ubiquitous, and it occurs in the first place because it

serves a useful cognitive and communicative function. … Metonymy allows an efficient

reconciliation of two conflicting factors: the need to be accurate, i.e., of being

sure that the addressee's attention is directed to the intended target; and our natural

inclination to think and talk explicitly about those entities that have the greatest

cognitive salience for us. By virtue of our reference-point ability, a well-chosen

metonymic expression lets us mention one entity that is salient and easily coded,

and thereby evoke - essentially automatically - a target that is either of lesser

interest or harder to name. In view of Mbeki's dream of an African Renaissance,

the deictic use of the pronoun first person singular, as a cognitive reference

point (and a vantage point-shift mechanism) within the metonymic expression I

am an African, conceptually maps different categories onto the concept African.

Exploitation of the conceptual blend African Renaissance would be trivial

if different groups are not solidified into the expanded group referred to by the

secondary deictic expression we (as Africans), explicated by his claim: (24) The constitution whose adoption we

celebrate constitutes an unequivocal statement that we refuse to accept that

our Africanness shall be defined by our race, colour, gender or historical

origins. 6. The conceptual blend African Renaissance Although Mbeki never uses the expression African

Renaissance in this address, he clearly hints at it, if we consider this address

against he background of his address to the Corporate Council Summit (Chantilly,

Virginia, USA), in April 1997 - and consecutive addresses in this regard. Mbeki devotes the last eight paragraphs of this address

to the concept Africa, also attaching himself explicitly to Africa by the

use of the possessive my continent, when he starts this section of

his address with: (25) The dismal shame of poverty, suffering and

human degradation of my continent is a blight that we share. With this claim he introduces his dream of an African

Renaissance. Oakley (1998: 323/324) stresses the fact that

conceptual blending coordinates background assumptions with linguistic forms. Against

the background of the diagram in Figure 4, which encapsulates the process of conceptual

blending, we can summarize the process of conceptual blending in Oakley's (1998: 326)

words: Working over an array of mental spaces -

online conceptual packets built up as we think, talk, and understand - blending occurs

when two or more input spaces in cooperation with a generic space project

partial structure into a fourth space known as the blend. The blend

inherits partial structure from each input space and develops its own emergent

structure. Oakley (1998: 357) describes the generic space

as "a distinct mental space operating at a low level of description which can

provide the category, frame, role, identity, or image-schematic rationale for cross-domain

mapping." At this level Pauw (1996: 124) considers the generic space to

be more inclusive than distinct (as represented in the diagram in Figure 4), but

this argument will not be debated here. What is important, is the fact that once

a blend is developed, it functions "rhetorically as a new category and conceptually

as a counterfactual mental space that draws salient elements from other mental spaces",

according to Oakley (1998: 325). The conceptual blend African Renaissance involves

two experience domains (input spaces). Within his address Mbeki limits background

assumptions regarding Africa mainly to the following: "pain of violent conflict",

"dismal shame of poverty, suffering and human degration", and "a savage

road". These views relate to a general perception of Africa, expressed in the

words of McGeary and Michaels (1998: 39/40): The usual images are painted in the darkest

colors. At the end of the 20th century, we are repeatedly reminded, Africa is a nightmarish

world where chaos reigns. Nothing works. Poverty and corruption rule. War, famine

and pestilence pay repeated calls. The land, air, water are raped, fouled, polluted.

Chronic instability gives way to lifelong dictatorship. Every nation's hand is out,

begging aid from distrustful donors. Endlessly disappointed, 740 million people sink

into hopelessness. With regard to the other input domain, Renaissance,

Mbeki expresses a very unspecified view, relying predominantly on the force image-schematic

structure from the generic space: "Africa reaffirms that she is continuing her

rise from the ashes", "Africa will prosper", and "nothing can

stop us now". This image-schematic rationale instigates cross-domain mapping

on account of the fact that it relates to the perception of humiliating forces in

Africa. On account of the fact that he only implicitly introduces

the concept of an African Renaissance, Mbeki's address only paves the way for a very

rich emergent structure - a new category which should include background knowledge

about the European Renaissance, the previous three African "rebirths" (according

to Stephen Gray, in an interview with William Pretorius), namely the Caribbean generated

revival at the turn of the century, a rebirth that "was a movement towards black

dignity for all liberated people of African descent in the Caribbean"; the Harlem

Renaissance of the 1920s; and Pan-Africanism, "actively present with us as the

Pan-African movement post the Second World War, peaking in the 1960s." 7. Conclusion The Deputy President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki,

in his address to the Corporate Council Summit (Chantilly, Virginia, USA), in April

1997, referred to the concept of an African Renaissance towards which Africa is progressing.

This concept actually originated in the foregoing analyzed address, which he delivered

on behalf of the ANC at the adoption of South Africa's 1996 constitution bill. This

address was largely aimed at the introduction of the above-mentioned blend of an

African Renaissance as an underlying "ideology", although he did not use

the expression African Renaissance as such in this address. The need for this underlying ideology has to be considered

against presuppositions like the following: · The "new South

Africa" emerged from a very divided community, previously maintained by a policy

of racial discrimination. · The South African

"nation to be" constitutes a very diverse society; the acceptance of eleven

official languages suggests such a diversity, for instance. · South Africa would

presumably not be able to prosper within a continent where deterioration prevails. · A constitution

as such do not ensure collective prosperity. To aim at well-being and growth, a driving force

is needed. And very often an ideology serves as such an impetus for collective change

and solidarity. To establish and maintain a specific ideology, followers and potential

followers of the doctrines and beliefs of the ideology have to be manipulated - cognitively

and emotionally. The doctrines and beliefs of the ideology do not only constitute

the collective views, but, on a communicative level, propel the specific ideology

by way of linguistic and contextual variables, for instance. On a linguistic basis this article examined the deictic

foundation of such an ideology. It followed from the examination of the above-mentioned

address that linguistic manipulation enables a representative(s) of an ideology to

establish and maintain an ideology cognitively in different ways: · by coherent structuring

of the address as a macro speech act; · by the implicit

application of expansion and proximity forces; · by exploiting the

first person as a reference-point phenomenon; · by taking advantage

of vantage point mobility within and out of the deictic center, resulting in conceptual

identity transformations, categorization and recategorization; · by creating conceptual

blending on the basis of the integration of different vantage point and conceptual

frame phenomena. References Botha, Willem J. 1980. Die Grammatika

van die Eerste Persoon. Pretoria: University of South Africa (Dissertation). Crystal, David. 1987. The Cambridge Encyclopedia

of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Delport, Elriena. 1998. Die Koerantkop

as Kognitiewe Aanrakingsmoment. Johannesburg: Randse Afrikaanse Universiteit

(Thesis). Goleman, Daniel. 1996. Emotional Intelligence.

Why it can matter more than IQ. London: Bloomsbury. Langacker, Ronald W. 1993. Reference-point

constructions. Cognitive Linguistics 4-1: 1-38. Lyons, John. 1968. Introduction to Theoretical

Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mbeki, Thabo. 1996. The Deputy President's

Statement, on Behalf of the ANC, at the Adoption of South Africa's 1996 Constitution

Bill, 8 May 1996. The African Renaissance. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Occasional

Papers, May, 1998. Mbeki, Thabo. 1997. The Deputy President's

Address to the Corporate Council Summit - Attracting Capital to Africa, April 1997.

The African Renaissance. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Occasional Papers, May 1998. Microsoft. 1996. Excerpts from The American

Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Third Edition © 1996

by Houghton Mifflin Company. Electronic version licensed from INSO Corporation. McGeary, Johanna & Marguerite Michaels.

1998. Africa Rising. In Time, March 30, 39 - 48. Oakley, Todd V. 1998. Conceptual Blending,

Narrative Discourse, and Rhetoric. Cognitive Linguistics 9-4: 321-360. Pretorius, William. 1999. African Renaissance

- An Introduction. In Edge. Roodepoort: Technikon S.A., January 1999.: 22-24. Pauw, Marianne A. 1996. Die Ouderdommetafoor

in die Afrikaanse Poësie. 'n Kognitiewe Ondersoek. Johannesburg: Randse

Afrikaanse Universiteit (Thesis). Radden, Günther. 1992. The Cognitive

Approach to Natural Language. In Pütz, Martin (ed.), Thirty Years of Linguistic

Evolution. Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 513 - 541. Rautenbach, Ignatius M. & Erasmus F.J.

Malherbe. 1998. Wat sê die Grondwet? Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik. Richards, Jack, John Platt and Heidi Weber.

1985. Longman Dictionary of Applied Linguistics. Essex: Longman.

Figure 4. Conceptual constellation

underlying the I am an African-metaphor